In many areas, when the ocean water is disturbed at night, it sparkles with a spectacular blue light. It has long been known these flashes are caused by tiny plankton known as dinoflagellates. However, a new study has for the first time identified the potential mechanism for this glow.

The study by a team of scientists, including University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science (UMCES) Professor Dr. Allen Place, was recently published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. It proposes that the key to making these microscopic marine plankton glow involves voltage-gated proton channels—avenues inside the single-celled organism’s membrane that can be opened or closed by chemical or electrical events.

The red tide that was recently flashing off some California waters is generated by plankton blooms. Although the California species may be different from those included in this study, their mechanism for triggering flashes is believed to operate by the same mechanism.

“The proton channel is the electrochemical mechanism that allows protons to flow across membranes in a gated manner,” said Dr. Allen Place of UMCES’ Institute of Marine and Environmental Technology, who was one of the authors. “It is used by some dinoflagellates to trigger light production in the familiar blue flashes we see in the oceans.”

As reported by the National Science Foundation, study team member J. Woodland Hastings suggested the presence of voltage-gated proton channels in plankton almost forty years ago. But the team only recently confirmed them by the identifying and testing plankton genes that are similar to genes for voltage-gated proton channels that have been identified in humans, mice and sea squirts.

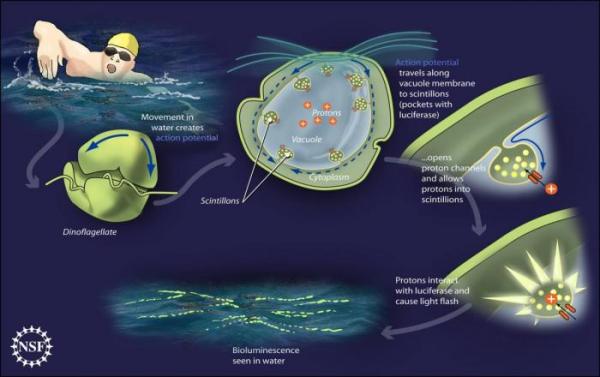

According to the study, here is how the light-generation may work:

The movement of ocean water jostles floating plankton, triggering electrical impulses around an internal compartment in the organism called a vacuole--which holds an abundance of protons. (See accompanying illustration.) These electrical impulses open voltage-sensitive proton channels that connect the vacuole to tiny pockets that dot its membrane.

Once opened, the channel funnels protons from the vacuole into the membrane pockets, activating a protein called luciferase, which produces flashes of light that are captured and stored. This bioluminescence would be most visible during blooms of plankton where there is an abundance of organisms in one area.

Source: National Science Foundation

Proposed bioluminescence mechanism in dinoflagellates.

Illustration by Zina Deretsky, National Science Foundation.

Blue tide photo by Phil Hart.