Thousands of Marylanders with their eyes on the water have helped scientists understand when bottlenose dolphins are visiting the Chesapeake Bay. Researchers at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science launched the Chesapeake DolphinWatch App in 2017 to get real-time reports of dolphin sightings on the largest estuary in the United States. Over the past five years, researchers have used these sightings—submitted by over 12,000 Chesapeake Bay community members—to help track the patterns of dolphin visits to the Bay.

In 2015, bottlenose dolphins were thought to only be summer visitors to the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries, but after releasing underwater microphones (called hydrophones) in the Patuxent River, UMCES Research Professor Helen Bailey discovered there were more frequent sightings and detections than they had expected. This discovery sparked interest by researchers, who were curious to know just how often dolphins were visiting the Bay and where they were venturing.

“We realized because the Chesapeake Bay has so many people, due to the way its shaped and the communities that are there, we had an observation network. If we could tap into it, we could collect that data,” said Helen Bailey.

The Chesapeake DolphinWatch app was created to allow people who are already enjoying the Chesapeake Bay to report sightings of dolphins including the time, date, GPS location, number of animals observed, and pictures and video of the animals throughout the Bay, creating an unprecedented observation network.

Once sightings are submitted through the app and verified by a team member, UMCES researchers compile the data and track trends in regional bottlenose dolphin occurrence. An average of 1,000 sightings were reported per year in 2017 to 2021 with the highest number being more than 1,400 dolphin sightings reported in 2022. So far this summer, there have been 1,283 unconfirmed sightings.

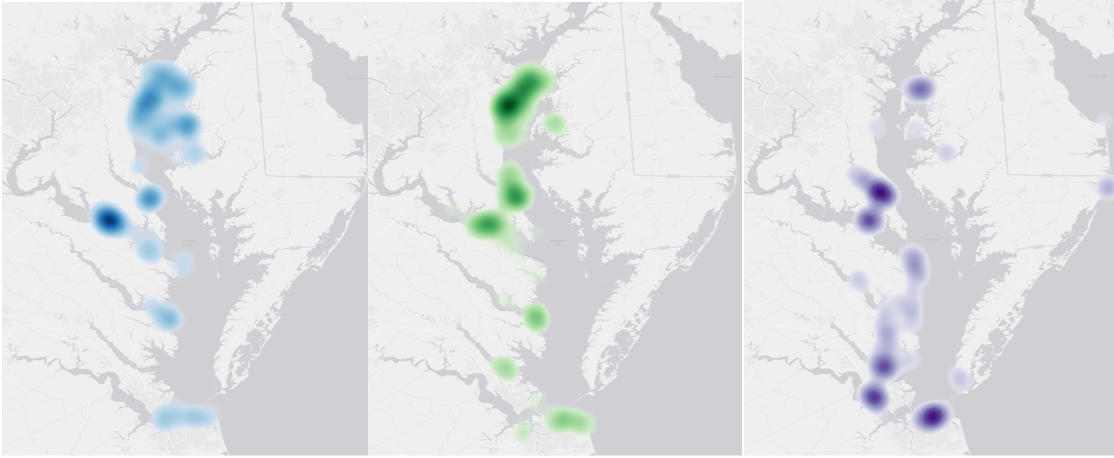

Dolphins sightings and acoustic detections peak annually in July around the Chesapeake Bay, as well as at the mouths of multiple tributaries, including the Potomac River, Rappahannock River, and the York River.

View an animated map of dolphin sightings in the Chesapeake Bay over the years.

Using data collected by community science reports and hydrophones, UMCES graduate research assistant Lauren Rodriguez released a study in 2021 explaining the patterns in dolphins’ seasonal movements. Now, she is shifting the focus of her research towards using DNA to study how dolphins interact with the species they eat.

“By taking a water sample near dolphin pods, we are able to identify the fish species that reside alongside them—kind of like underwater forensics. This helps figure out why dolphins are coming into the Chesapeake Bay, and it can also further inform species management,” said Rodriguez.

Cataloging dolphins in the Chesapeake Bay is a group effort. The DolphinWatch team not only tracks dolphins’ patterns from the community but also submits users’ photos to the Mid-Atlantic Bottlenose Dolphin Catalog, a part of OBIS SEA MAP (an ocean biodiversity information system) for dorsal fin identification and matching.

“I hope that dolphin sightings, and the increased awareness that Chesapeake Bay is a bottlenose dolphin habitat, will inspire community members, natural resource managers, and policy makers to continue their work in Chesapeake Bay conservation and push forward restoration goals across the board,” said Chesapeake DolphinWatch Coordinator Jamie Testa.

Interested in learning more about or supporting Chesapeake DolphinWatch? Check out their website and find regular updates on their social media.