Since its founding, the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science’s work has lead to groundbreaking discoveries that have changed the way we think about our environment. The pace continues today as cutting-edge research focuses on important issues—from turning algae into biofuel to predicting the impact of climate change—to provide a scientific foundation key to planning for our state and nation’s future.

Nitrogen fertilizers make it possible to feed more people in the world than ever before. However, too much of it can also harm the environment. Xin Zhang and Eric Davidson of the Appalachian Laboratory has been leading a national group of scientists, economists, sociologists, and agriculture experts in figuring out how to produce more abundant and nutritious food while minimizing pollution and giving farmers a chance to make a living. He calls it “Mo Fo Lo Po”: more food, low pollution.

In Maryland, Tom Fisher of the Horn Point Laboratory is working directly with farmers and residents on the Eastern Shore to measure the impacts of best management practices like cover crops and stream buffers on water quality. The People Land Water project is a five-year study meant to determine the effectiveness of such practices on agricultural and residential properties.

Exploring advances in alternative energy

UMCES scientists are leading the way in studying the impacts of energy sources on our environment.

Ed Gates at the Appalachian Laboratory is monitoring how wind turbines in the mountains of Western Maryland are affecting bats and birds.

Helen Bailey of the Chesapeake Biological Laboratory is using underwater microphones to figure out when whales, seals, and dolphins are traveling along the Atlantic coast to recommend the best times to construct wind farms to minimize impact on marine life.

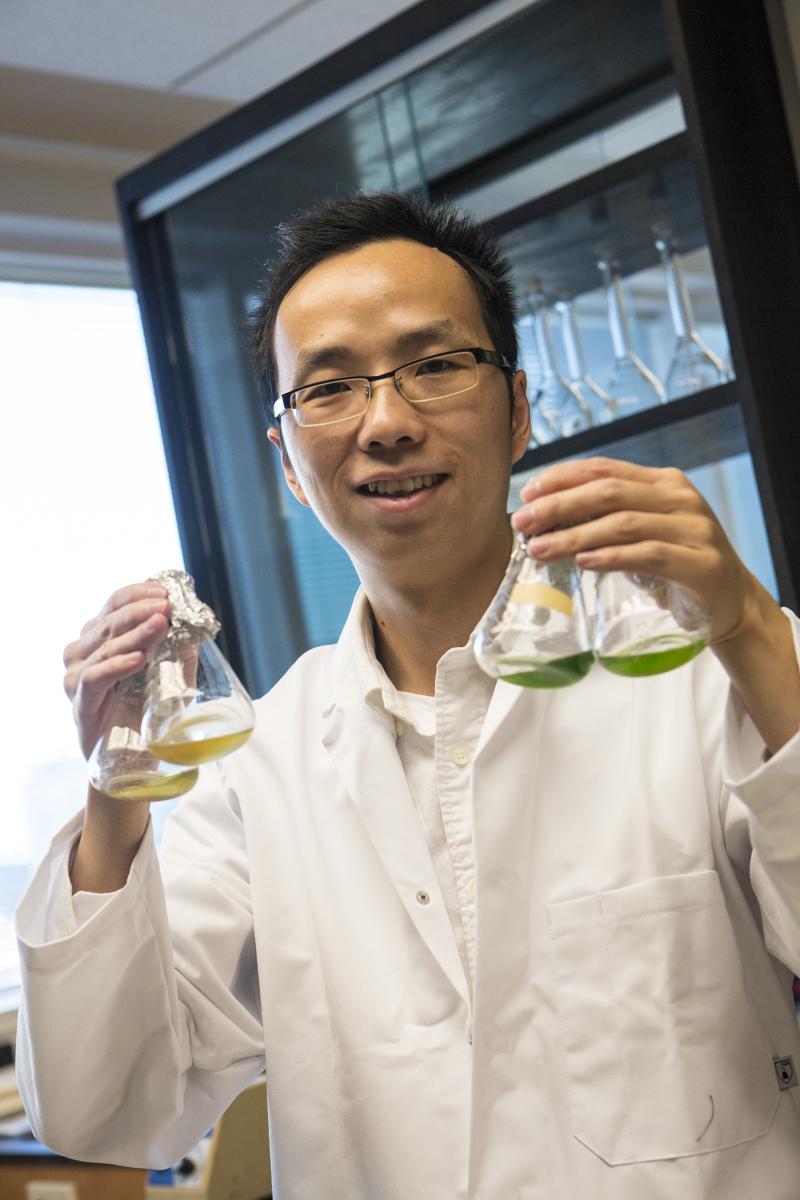

In the laboratory, Yantao Li is working with colleagues at the Institute of Marine and Environmental Technology to make the development of biofuel more efficient by identifying an oil-abundant strain of algae and perfecting an economical method to extract it for use.

Declines in the Chesapeake Bay blue crab stocks led Maryland to search for scientific answers and effective management responses in the mid 1990s. Tom Miller of the Chesapeake Biological Laboratory played a leading role in examining the condition of the Bay’s blue crab population through laboratory, field, and modeling approaches, setting in motion actions that dramatically changed our understanding of blue crab population dynamics and led to successful Bay-wide changes in management.

Sook Chung at the Institute of Marine and Environmental Technology is looking at crabs from the inside out, examining how their genes and hormones impact how they reproduce and survive, potentially impacting a healthy stock in the future.

Understanding a changing climate

To understand how our climate is changing today and what could happen in the future, scientists like paleoclimatologist Hali Kilbourne at the Chesapeake Biological Laboratory turn to natural archives such as ancient corals to see how the Earth’s climate has changed in the past. Corals keep a climate record in their fossilized skeletons that can be plugged into a model to help predict changes in the future.

Meanwhile, Matt Fitzpatrick and his colleagues at the Appalachian Laboratory are taking a step into the future by peering into the genetic blueprint of living trees, and combining new modeling approaches with satellite imagery, to make predictions about how species will react to a quickly changing climate