It started with a mystery.

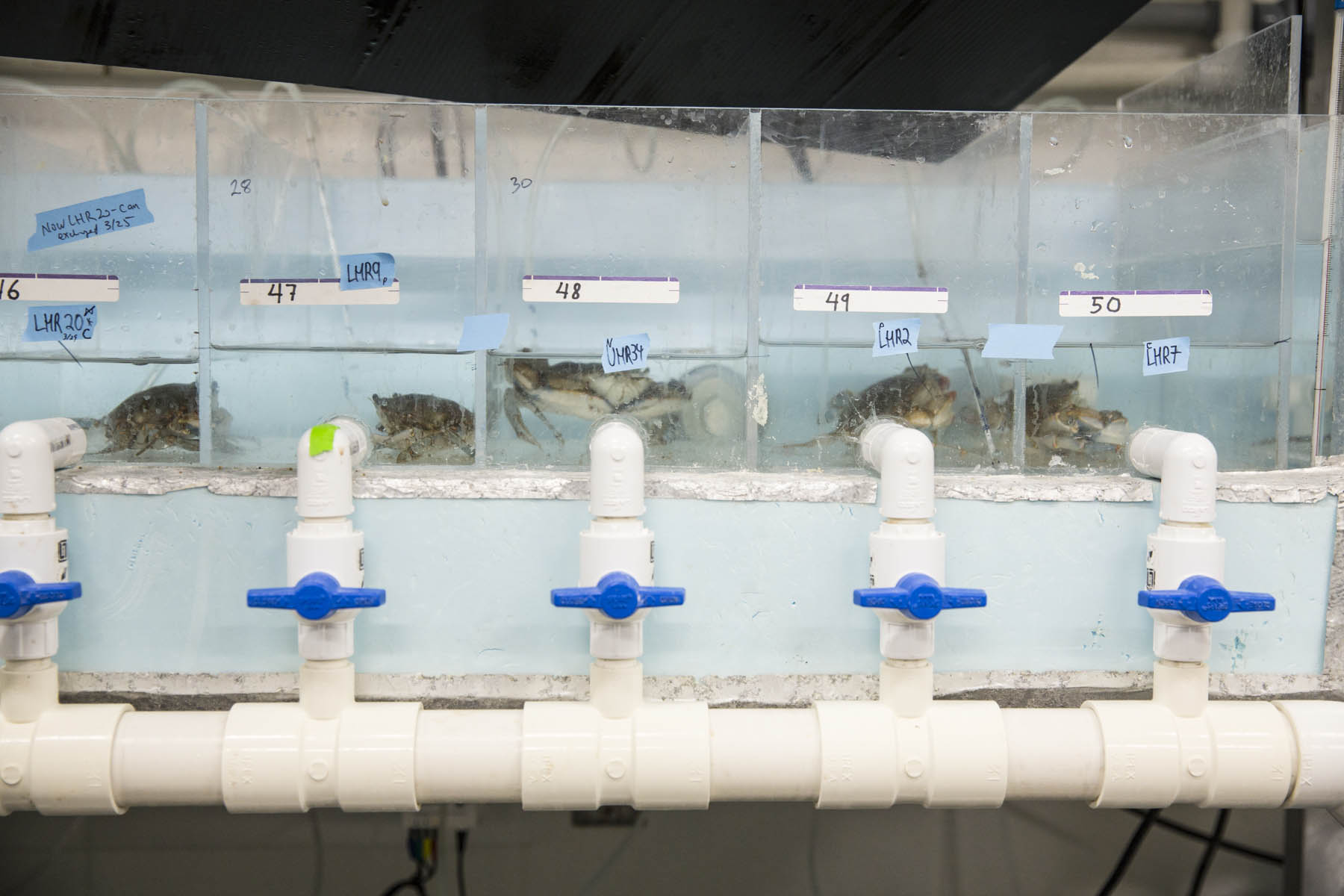

The vast majority of blue crabs brought into the aquaculture center at the Institute of Marine and Environmental Technology died within months of their arrival, but there was no real indication of what killed them.

Some considered water quality the culprit, but molecular biologist Eric Schott looked at the issue another way, or as he put it, “through the disease lens,” and found something unexpected. He had spotted a virus—first described in the late 1970s, but not so closely linked with so much mortality—that he would spend roughly the next decade researching.

“I think forever people have seen that crabs die in captivity, and they attributed it to a lot of things, including stresses. That’s partly true because if it didn’t have the stress, it might not die and if it didn’t have the virus, it might not die, but when you put them together, you end up with a dead crab,” Schott said.

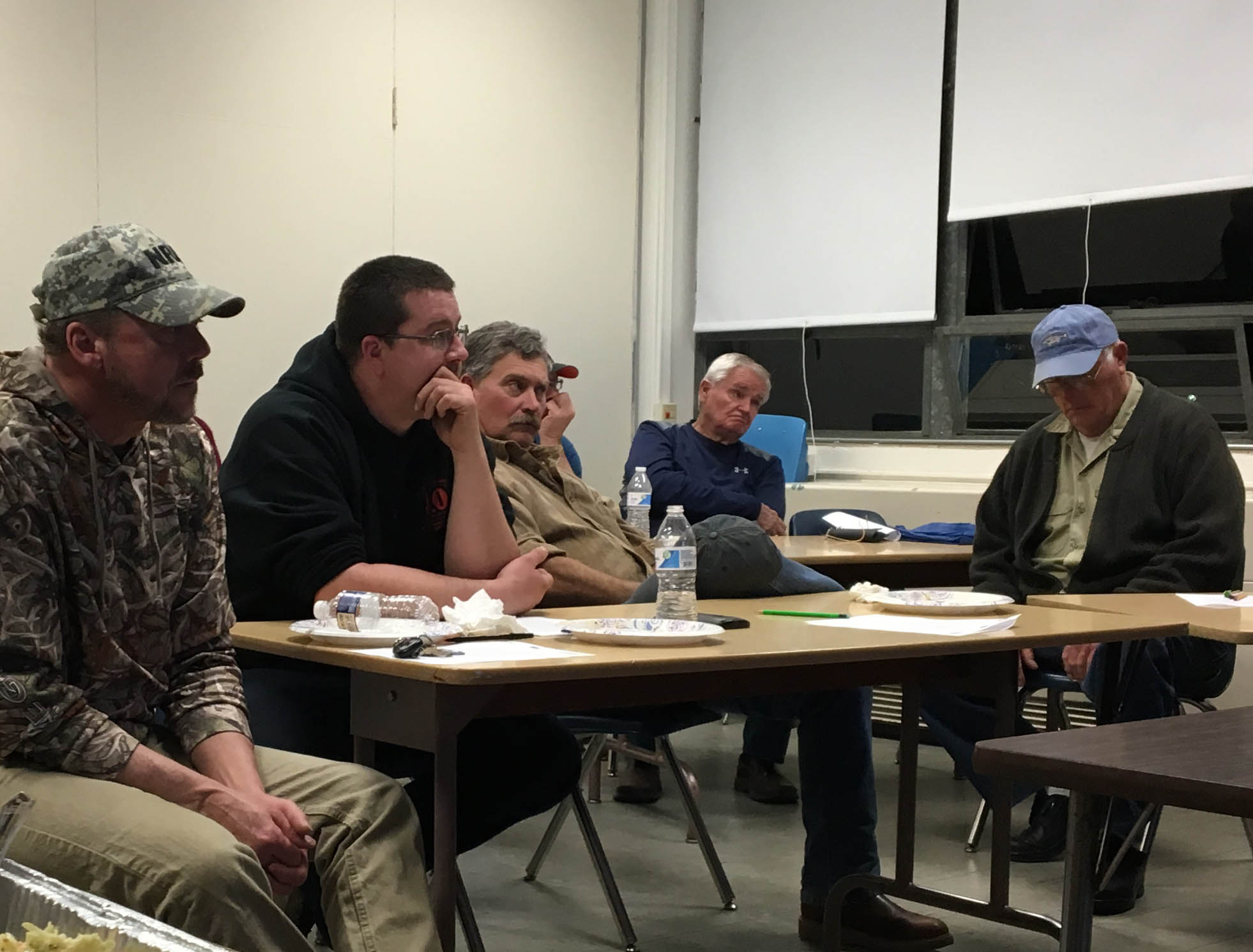

In February—about six months after wrapping the first year of a study of this reo-like virus alongside watermen in Maryland, Virginia, and Louisiana—Schott hosted a crab industry shedding workshop in Galesville. Blue crab reovirus is pathogenic only to blue crabs and poses no threat to humans.

On average, his and other studies found, 20 percent of the blue crabs pulled from the water and held for soft shell production were dying before they got to market.

Almost all the Chesapeake Bay crabs that die during soft shell crab production have high levels of this virus, but having the virus isn’t a death sentence for the crabs, Schott explained. The virus only proliferates when you have animals under stress, such as shedding, injuries, being held in captivity too long, and water temperature fluctuations.

At the workshop, Schott discussed what he learned about the disease’s prevalence, its impact on soft shell production, and what triggers it from dormancy to kill.

“On average, 20 percent of the crabs die in soft crab production, but it’s not always that way,” he said. “The discovery of the virus refocused our attention on the mortality; the virus seems to be killing them when it’s combined with one of these stresses (that the watermen are in control of).”

Schott hopes the lessons he shared at the February workshop, and plans to discuss at future meetings, can help watermen cut down the number of deaths in the crabs they catch and make the fishery practice more sustainable.

“If you can make sure that every crab that comes out of the water makes it to market in some way that’s the best outcome,” he said.

During his summer study, Schott said they investigated different crab shedding systems along the Chesapeake Bay in Maryland and Virginia to determine what the successful ones were doing that others could imitate.

They determined the amount of time crabs spent in the tanks between being caught and sold and the temperature of the water in the tanks appeared the most important factors in saving the most crabs.

The value of soft shell crabs—about three times their hard shell worth—makes producing them a highly sought practice. Schott estimates about 5 to 10 percent of the fishery goes to soft shell production in the Chesapeake.

Crabs must discard their shell in order to grow. For a brief few hours after breaking out of its old shell, a newly molted crab is soft enough to be cooked and eaten whole. Fishermen can produce soft crabs by identifying pre-molt crabs and holding them in shallow tanks until they "shed." When refrigerated, newly molted crabs stay soft for several days.

The color on a margin of a crab’s swimming fins serves as a signal to help the watermen determine if it’s worth holding for a soft-shell sale, Schott said. Green can mean a 10-day wait until that crab will shed its shell and white is nearly as long. Pink means it’s getting closer and red means it’s one to two days away from shedding.

A crab put in the tank too early is at more risk of dying there.

“You can expect if they’ve taken it when it’s 10 days away from molting, the chances that it’s going to die before you get a soft crab out of it are increased,” Schott said. “For one, it’s not feeding. It’s also stressed.”

Water quality once the crabs are caught is as critical to monitor. Many of the shedders Schott spoke with have thought about nitrogenous waste and monitoring levels of ammonia in the tanks, but some hadn’t realized how much temperatures fluctuated and what affect that had.

In one of the facilities they surveyed during the summer study, they saw the water temperatures went from 63 degrees to 87 and then 69 in a 24-hour period.

“These 20-degree temperature fluctuations every day, that’s a stress. In the Bay, they’re going to have a much more stable temperature,” Schott said.

Maintaining water temperature by shading the system or using a big reservoir so you have more stable temperature could cut that stress, he added.

The study also showed that shedding systems perform differently and had varying effects on the crabs kept in them. Recirculating systems, which have water pumping through a bio filter, had 14 percent mortality compared to 32 percent mortality seen in flow-through systems, which take water in from a local creek before pumping it back out.

About a dozen people attended the workshop, allowing a good conversation to flow, Schott said. He and collaborators will host another shedding workshop in Virginia in April, and one more is planned for Maryland’s eastern shore.

There haven’t been workshops like the one he held about shedding in Maryland in decades, Schott said. While the virus led to this recent meeting, he feels there’s value to holding them more regularly to help establish and encourage best practices.

“What we’re doing is we’re taking the discovery of the virus and its tight association with mortality as a reason to revisit all those other things that we should be doing anyway, which is maintaining your temperature and water quality,” he said. “It’s basically making old information new again, but we get to look at it through the lens of the disease.”

Story by Kristi Moore